The Kalam and the Missing Lawnmower

Does the universe have a beginning? If we conclude that it must have a beginning in time, it becomes more difficult to believe that the universe was not caused to exist by a timeless creator. We do not need scientific evidence that the universe had a beginning. I’ve offered some of the scientific evidence elsewhere but here I would like to offer one of the simpler philosophical arguments for this claim.1 This is a particular argument for a premise in the Kalam Cosmological Argument for God’s existence (herein simply, the Kalam).

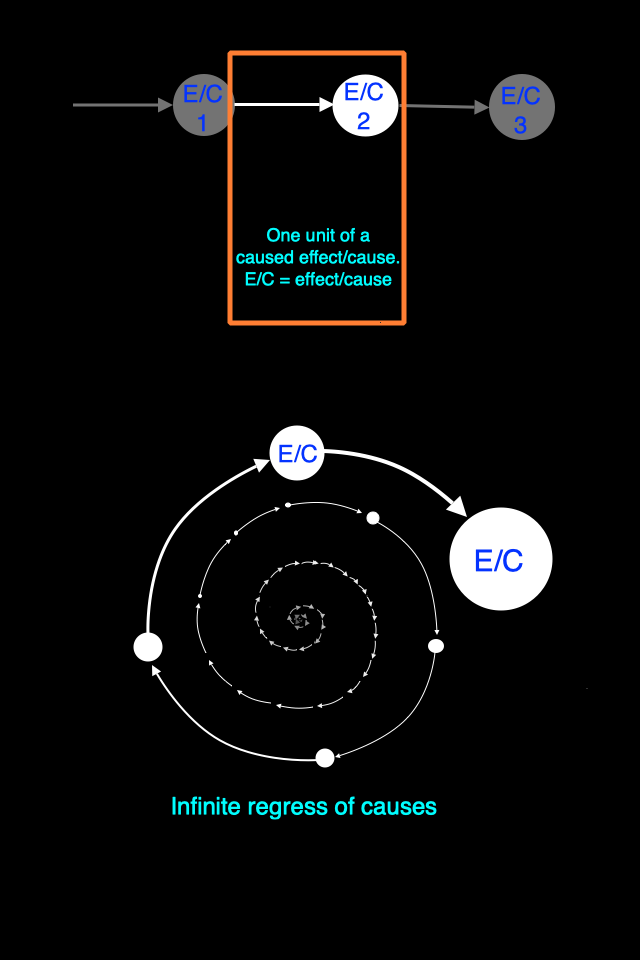

All change involves cause and effect. For normal causation, what we may call mechanistic causation, each effect has a previous cause and each effect can also be a cause to another effect. Let me call this basic unit of the causal process a “caused effect /cause.” So given normal mechanistic causation, for any event or change that occurs, there had to be an infinite regress of causes, an infinite number of events occurring sequentially into the beginningless past. That's what we're stuck with unless we start with a cause which has no prior causes. I believe that if we understand this infinite regress of causes, we should be able to see that it cannot occur, that there had to have been a first cause uncaused by any prior cause. The problem is that many people do not see this impossibility. Let me bring up an illustration that may help us to grasp this.

Imagine that B were my neighbor and I ask to borrow his lawnmower. B doesn't have one but he asks his other neighbor, neighbor C. C doesn't have one but she asks her other neighbors, D. D doesn't have one but he asks E. Now suppose this goes on and on with each neighbor asking another neighbor. If I have an infinite number of neighbors and none of them has a lawnmower, I'm never going to get a lawnmower.2

Now this illustration differs from what we think of as mechanistic causation which involves an infinite series of events completed in the past. The lawnmower illustration suggests a task, asking neighbors, which will continue into an infinite future. So suppose we change our story so that we remove this time issue and make it a little more like the causation scenario. Suppose that the amount of time it takes to ask B to borrow his lawnmower and the time B responds is eight seconds. Suppose that somehow when this same segment of finite time begins, B asks his neighbor C and C asks D, and so on. I’m qualifying this illustration in this way because I think it would be easier to visualize and to grasp the conclusion I want to make. So this infinite number of askings and responses all occur within the same finite segment of time that I first ask B, my first neighbor, and B responds—about eight seconds. The rule, remember, is that one may not have a lawn mower unless it is borrowed. What we should see is that even with an infinite line of borrowers, because no one will have the lawnmower unless it is borrowed, no one will have a lawnmower. We never have someone responding to the question with, “Sure, here’s a lawnmower you can borrow.”

Likewise not one of these infinite number of effect/causes has in itself the power to exist on its own since each one needs a prior cause to exist. So if we have an infinite number of caused effect/causes, then none of these effect/causes could have ever come into being, none of them could ever exist. Just as no one has a lawnmower, so we cannot have a caused effect/cause. Even if we hypothesize an actual infinite line of completed caused effect/causes, an infinite number of past cause/effect events, they cannot actually exist just as there can be no lawn mower if it must be borrowed by and from an infinite number of borrowers and (mowerless) lenders. It is the nature of these dependent entities that makes their existence impossible even if the number of these sequentially dependent entities are infinite. So there does need to be an uncaused first cause, a cause which is not itself an effect from a prior cause. If in its original, primordial nature the first cause changes, if it were a changing entity, then it would not be a first cause, it would just be another effect/cause which itself exists as the final product of an infinite regress of causes (which we have seen cannot occur). There must be some prior point in time before which it is unchanging (and thus is in itself timeless) even if in this state of timelessness it (timelessly/changelessly) chooses to enter time. So it must ultimately be timeless.

We experience uncaused causes in our own free human choices. We ourselves are the cause of those choices with nothing other than or prior to ourselves causing us to make those choices. If God is defined as at least a conscious person, a timeless God or source of the universe existing without the universe, it could choose for the universe to exist without that choice being caused by anything prior to God or other than God. That can make sense, but it doesn't make sense to imagine an infinite past for our changing universe.

If the universe had a beginning, nothing else could explain it as adequately as a personal source of the universe. There cannot be a non-conscious first cause, because all non-conscious causes have prior causes which they need for that non-conscious cause to exist. Try to imagine a non-conscious first cause. What mechanism can it have to get the universe going? Any mechanism we can think of exists prior to it and causes the non-conscious cause to produce an effect. And that prior mechanism has itself another prior cause, and so on for ever. On the other hand, a conscious first cause, if it is timeless, we can imagine having always existed and having always chosen for the first change to occur and thus the beginning of time to occur. If we cannot say that it always existed, then we can at least say that it timelessly has existed.

Here again are the alternatives:

1) The universe can go on into an infinite past. Cause and effect producing change and motion goes on for an infinite past.

2) It can have a beginning from a changeless, non-conscious first uncaused cause.

3) It can begin with a timeless (that is, changeless) conscious first uncaused cause.

1) is excluded because of the nature of cause and effect, as we’ve just seen.

2), a beginning with a non-conscious first cause does not work because it is inert, there is nothing in itself which can get it going to cause anything else. We have no experience of a truly unchanging non-conscious entity initiating change, nor can we conceive of such a thing.

3) is the only possibility. Only a timeless conscious first cause can work to bring about change. We have no direct experience of a timeless conscious first cause, but it is perfectly conceivable. This would not require that this first cause be timeless once a temporal universe is created.

I would conclude with a conscious first cause of existence. It must have sufficient power to bring about the existence of the universe. Thus it must have very great power from our vantage point. It must also have very great intelligence, at least the intelligence to bring about the existence of the universe such as it desires.

There are other philosophical arguments which are commonly discussed which claim that there cannot exist an infinite number of past events each completed within a finite amount of time. The reader may be interested in looking at these arguments as well.3

A second independent argument for a conscious first cause.

I have one other argument that the first cause is a conscious entity. This argument is independent of the one just presented other than the requirement that there must be a first uncaused cause (as argued above).

First think about what consciousness is, what mind is. We normally think that any material object is not aware of anything. My phone may be able to record sounds and make videos but it is not aware of those sounds or images or anything else. Now you and I are aware of visual sensations and auditory sensations, what we hear and see. We are aware of the physical world around us. So our universe is made up of more than just brute material objects which are not conscious. Our world includes this unique characteristic of consciousness in at least one species of animals, humans, and likely some others as well. Our awareness of things, of material objects, of others, of ourselves—this awareness is radically different from the senseless material objects themselves. They are so completely different that they make up two categories of existence: the awareness, the consciousness of other things, and those things which are not conscious. When we grasp this radical difference, we see that consciousness cannot come from a non-conscious object; it cannot come from an object insofar as it is not conscious, no matter how complex that material object may be. It may be the most complex computer imaginable; it may even have the extreme complexity of a human brain. Mindless matter alone cannot be transformed into something possessing mind unless mind, consciousness, is somehow already present in the world, unless that mind is somehow accessible so that it can inhere in that matter as it does in the human brain. That’s why I think that the science-fiction assumption that someone can create a conscious robot from matter alone, an android like Star Trek’s Commander Data, say, is simply impossible.

But now if the universe needs a first cause and if part of what constitutes this universe is consciousness, then that first cause must possess that characteristic of consciousness in order to give it. Since the material universe needs a first cause, so the conscious portions of the universe would need it as well. Consciousness cannot come from the unconscious portion of the universe—as I’ve just shown—so it must come from the first cause, the uncaused cause of the universe. If the first cause of the universe is not conscious, then we could never have consciousness in the universe. We would just have a universe of mindless objects which came from some entity which was a first cause but which did not impart mind or awareness to anything. We have just seen in my previous argument that a mindless first cause could not exist, a non-conscious entity would not be able to produce a first cause. But independently of that argument, we should see that even if we could have a mindless first cause that could cause this universe to exist, it could not account for the consciousness we find in the universe.

My conclusion: there must have been a first cause of the universe uncaused by anything else and it must have possessed mind or consciousness.4

Notes

1. I’ve updated my article on scientific evidence for a creator on this website which included the argument discussed here but in a shorter form. My hope is that by focusing on this argument by itself without the scientific evidence but with the included illustrations, the force of the argument will be more evident.

2. This illustration and argument was, to my knowledge, originally offered by Richard Purtill, Reason to Believe (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1974), 83–87.

3. For a fairly simple presentation of several arguments against an actual infinity see William Lane Craig, On Guard for Students: A Thinker’s Guide to the Christian Faith (Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook. 2015), ch. 3.

A more technical presentation may be found in W. L. Craig and J. P. Moreland (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), ch. 3, sections 2.1–2.2.

Paul Copan and W. L. Craig (eds.), The Kalam Cosmological Argument, Volume 1: Philosophical Arguments for the Finitude of the Past (New York, Bloomsbury Academic, 2018) is an anthology of arguments for and against this thesis.

4. I have one objection which is insignificant enough to relegate to a footnote.The consciousness we find in our world, though we may conclude that it must come from a first cause, need not be as developed as what we find in humans. As such, given the second argument alone, the first cause cannot be known to have any greater degree of consciousness than the lowest sentient animal created. The lowest animal life, say something like an amoeba, we can be reasonably sure has no awareness. It may be much more like a simple machine programmed to avoid certain chemicals and to move toward and ingest certain others. The first stage of consciousness, call it stage one or (1), might be found in an animal which is actually aware of phenomena, perhaps with a simple eye, but is unable to think about those perceived shapes and motions and shades of light and darkness. This organism too responds to the perceived shapes and motions by programmed responses, by a kind of simple instinct. It is only aware of the sensa, not of that sensa as distinct objects or entities. It may feel tactile sensation but it responds to, say, caustic chemicals or temperatures or the bite of a predator by its programming which causes it to move away from the danger. If it feels pain (it need not), it does not react to the pain but only reacts as it is programmed. Though this organism has a simple sentience, it is not significantly different from the non-sentient organism. Of course we do not know whether there are any living organisms in this unique condition. The next stage (2) might be an organism which perceives sensations and has some awareness that these are objects and entities in its surroundings. However, it is not aware of itself as a distinct entity that perceives these objects. Many animals may fit this category. The final stage (3) is a conscious being aware of its surrounding world and of itself as an entity that perceives. Humans are self-aware and possibly some higher animals are as well. In our earlier Kalam argument, we assumed what we call here a type (3) consciousness in the first cause, the uncaused cause. Organisms with any of these three may or may not experience pleasure and pain.

Could we have a natural evolutionary progression from (1) to (3) by merely increasing one’s intelligence? If so, the first cause could have no more than the sentience of (1) (or something like it) and the progression to (3) in humans could occur by a simple evolutionary increase in mechanical intelligence. If we have no more than this, we have at least a first cause with consciousness, even if only something like a consciousness (1). This is a definite progression from a non-conscious first cause. Some critics of the Kalam will admit that the argument does prove a first cause but will protest that the first cause cannot be conscious. Belief in a non-conscious first cause is now found to be untenable (as it has with our first argument). However, we do face a problem with this conclusion when we consider that the first cause, if it alone exists, would have nothing else to be aware of than itself. So it would be aware of itself but not of anything else. But then if it intends to create, it must be aware of that which it thinks to create as well with a type (2) consciousness. Thus it must have a full (3) self-conscious existence since it is also aware of itself.

It may be difficult to see that a natural evolutionary increase in intelligence can produce the changes from (1) to (2) to (3) in animals. The changes from (1) to (2) to (3) may appear to involve a new kind of consciousness with each change. If so, the first cause must have the full type (3) consciousness; that is, it is aware of itself and that which it intends to do and create. Thus it can provide each form of consciousness as it is needed in creation. If a natural evolution can account for the progression from (1) to (3), then we still see that the first cause must have the full (3) consciousness as our previous argument demonstrates.

Note: If the images in this article are not available on your display, they may be described as follows:

Image 1: Three circles respectively contain the symbols E/C1, E/C2, and E/C3 and each has an arrow pointing to it, E/C3 from E/C2, E/C2 from E/C1 and E/C1 from an unseen prior E/C. E/C2 is isolated in a box to indicate “One unit of a caused effect/cause. E/C= effect/cause.” Below this figure is a spiral of circles and arrows, each circle containing the letters E/C or suggesting that it is an E/C. Each E/C circle, except for the very last one, has an arrow pointing to the next one. The spiral suggests an infinite number of E/Cs (effect causes) coming from a beginningless past. The spiral is labeled an “Infinite regress of causes.”

Image 2: The first picture in this image shows the silhouette of two people, neighbors, talking. The first asks, “Could I borrow your lawnmower?” The second answers, “I’m sorry but I don’t own one. But let me ask my other neighbor.” Overhead is a timeline from t1 to t2 indicating a given amount of time passes for this conversation. Below this picture is another smaller one of the second neighbor asking this same question of a third neighbor and receiving the same answer. The time line above the speakers’ heads indicates that the same segment of time is being traversed in this conversation as in the first one. A third and smaller image below this one has the third neighbor asking a fourth one the same question and receiving the same answer. This continues—the fourth neighbor asking the fifth, the fifth asking the sixth, etc.—with a spiraling line of images indicating an infinite number of conversations with this same question and answer. Each, though of course physically impossible unless the nature of time can be altered, occurs within exactly the same completed segment of time.

Dennis Jensen, October 2019; minor additions August 2021; second consciousness argument added January 2024.